Editor Note: This piece is loosely based on real places and events, but the characters are fictional. It’s part of a series of stories about the growth and development of Portland culture. I really don't have a tattoo.

~

Lauren and Sara sucked down their Cape Cods at Casa U-Betcha, a gaudy Mexican bar heavily decorated with a Day of the Dead theme. In the turquoise bathroom, they made final appearance adjustments – Sara adding another layer of mascara and smoothing her wine-red bob, Lauren rubbing on lipgloss and fluffing the curly brown hair she modeled after Elaine on “Seinfeld.”

It took three steps to get down to the basement gallery underneath the restaurant, but it felt farther from the sidewalk. Up there, second-hand clothing sellers, vinyl record shops and smoky dives clung to life between espresso bars pushing caramel lattés, beauty boutiques promising lotions so natural you could eat them and a pizza parlor known for its Thai chicken topping.

Below, next to a metal rack dripping with coats, an elfin attendant handed out cards that read: “Please, do not speak to the models.”

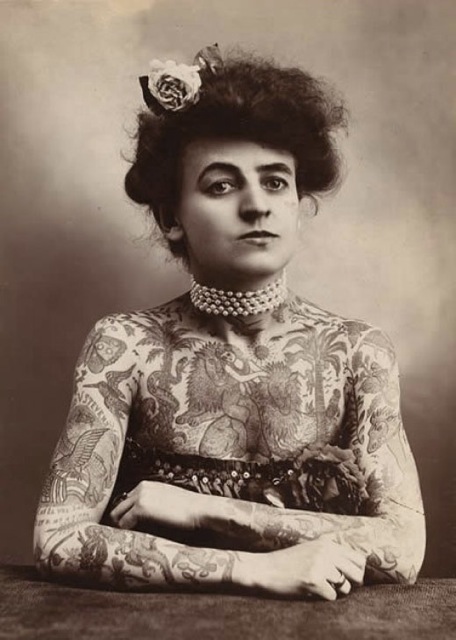

Bare walls bore the bent nails and scuff marks left by previous, more typical art openings. For this show, 11 nearly naked elderly people lined the room’s edges. Six on one side, five on the other, they didn’t directly face one another; each sat in a wooden, high-backed chair. In plain underwear and thin towels, they might have been waiting for medical treatment. But, at “Vintage Tattoos and the People Who Wear Them,” these people were the attraction.

Under loose skin, mottled spots and awkward lumps, the blurred and faded tattoos commemorated long-dead mothers and crumbled love affairs. Ships once sailed and mottos formerly believed. Characters appeared from discontinued comics: Betty Boop, Popeye, King Kong. The models stared blankly into the quiet room like guards at Buckingham Palace.

The first “exhibit,” just to the left of the entry, was a bony woman with a silvery bun perched on her head and wearing a thick black bra and matching underwear. Jungle tattoos covered her body from neck to wrists to ankles, with green vines creeping up to her chin and tugging down the soft skin around her jaw. Strange birds and angry-eyed primates peeped through the leaves.

“She must have been in the circus,” said Lauren. “Why would you do something like that to yourself?”

Lauren worked in a law office, but wanted to be a writer. As a fan of Roald Dahl, the show’s concept reminded her of “Skin,” one of Dahl’s adult stories. It’s about a down-on-his-luck Russian who realizes that the long-standing tattoo on his back was inked by the artist Chaim Soutine and he thinks that the portrait of his wife might now be worth something. Unfortunately for him, it is.

Just as that story drew a creepy haze over the action, Lauren felt uncomfortable in front of the models with her unblemished arms and legs revealed by her simple dark sleeveless dress. She already felt edgy from drinking on an empty stomach— the free chips and salsa at Casa were famously awful—but she grabbed a plastic cup of wine and folded her arms around herself. Her parents were so appalled by tattoos; she felt a little guilty just being there.

Sara sold cosmetics in a department store and didn’t want to do anything else, though she felt embarrassed about her lack of ambition. “I worked so hard for you to go to college,” her mother would complain.

But Sara loved performing makeovers on the women who visited her counter, and she had a knack for making the worn-out moms and over-stressed businesswomen look like happier versions of themselves. They always left with bags full of her products, but she worried they couldn’t keep to the routine at home.

As much as Sara enjoyed the disguise of makeup, she couldn’t understand why anyone would want to do something so permanent as to get a weak copy of the Mona Lisa reprinted down a bumpy spine.

“That is hideous,” she murmured to Lauren, her lavishly painted eyes striking in her pale face. This model straddled his chair, with his broad back facing the room. Tufts of wiry hair sprung along the tops of his shoulders and down back of his arms, making a sort of frame for the copy of the world’s most famous painting.

Sara’s dad had had several tattoos, including one with her mother’s name inside a heart, and her name and her brother’s tucked in along the sides. He had disappeared when she was 6, vanishing moments before the eviction notice hit.

Lauren and Sara continued around the room, making silly conversation about what kind of tattoo they’d get if they absolutely had to do it.

While Lauren thought the show might provide good material for some kind of story, Sara had wanted to come because she had a crush on the show’s organizer. Tim regularly perched at the tall Casa bar like he was waiting for an extremely important phone call and she felt more interesting just sitting near him. He hasn’t exactly invited her to the show, but he left a stack of postcards on the bar while she was there.

Lauren could tell Sara was looking for Tim as they moved around the now crowded room. They could pick out snippets of conversation.

“See that one with U.S.S. Iowa? My grandpa had that.”

“Wow, that guy looks like a chalk painting after it’s been through the rain.”

“Are those winning lottery numbers?”

At the far end, a guy with a massive frame made his chair look like it belonged in a kindergarten. He had a towel around his wide waist, and he could have been heading into a steam room to plot business with TVs falling from moving trucks, or which pony should finish third in the sixth. His skin was like a living cemetery, covered in names and dates and symbols.

With his big ears and eyes and hanging jowls, the man reminded Sara how her father used to tell her: “No matter how cute the puppy looks, don’t get a dog that will grow so big it could kill you.” She couldn’t remember much about her dad, but that had stuck with her.

“I wonder if my dad still has my mom’s name on him?”

“Maybe he covered it with a circle with a slash through it.”

Rachel had a tendency to joke when she got nervous.

When her parents annoyed her, Rachel considered getting a dolphin or sea turtle on an ankle. She found the endlessness of the ocean appealing. But it seemed too powerful a gesture for a family fight. She knew her parents would never get over it.

She wanted to ask the models many things: Were they being paid? How did they end up here? How did they feel now about what they had done? Would they do it again? But she knew she wasn’t supposed to ask questions.

~

“Vintage Tattoos” was the first of a three-part, one-night-only series Tim was producing over a couple of months. There wasn’t anything illegal about, “Body Modifications and What They Tell Us About Who We Are and Who We Want to Be,” but many, in and out of the art world, felt uncomfortable having people displayed in silence like sculpture. So after the tattoo show, Tim encouraged the models and audiences to interact. He specifically asked Sara and Lauren to come and talk to them, “think of things to say that will break the ice,” he asked. He didn’t want any negative attention to threaten his grant.

The second installment featured transgendered men and women—some dressed for one sex on top and the other on the bottom. Others wore revealing garments that did little to hide their non-conforming parts. Lauren tried to ask questions, but they made her feel stupid—“what bathroom do you go in?” seemed irrelevant, “don’t you feel like a freak?” too mean. In any case, they mostly wanted to probe each other for tips on the best hormone adjustments and stores that sold women’s high heels in size 12 wide.

Tim’s final spectacle featured dramatically pierced and altered body parts. Along with the expected stretched and distorted lips, eyebrows and earlobes, other “exhibits” offered more unusual looks, such as giant rings hanging from the nasal septum, which brought to mind bulls in a pasture.

Sara was drawn to a body builder, who posed with his unnaturally smooth and taut skin pocked by a dozen or so silver hoops in unexpected spots—the hollow behind his collarbone, the flap between thumb and forefinger, just above the hipbone. He looked proudly uncomfortable. She couldn’t think of anything to ask beyond, “Did it hurt?” The answer seemed obvious, so she just said, “Hi.”

Two women stood connected from nose to nipple by rings and a linked chain. They were spending three months strung together, they said, to represent the oppression of the patriarchal society.

Many of the subjects chatted easily with Lauren, telling involved tales about the pros and cons of their bodywork, including the challenge of making it through airport security with a pound of metal ball bearings packed into a scrotum.

Sara found the courage to ask Tim if he wanted to have dinner sometime. He looked at her like she was an exotic animal. “I’m sorry,” he said. “I’m not interested in emotional connections. I just like shocking people.”

xxx

As tattoos became more and more popular, Lauren and Sara found themselves an unmarked minority among their friends. Their friend Shelby in particular, a photographer at the local newspaper Lauren now freelanced for, tried to convince them to go under the needle.

With an ornate red dragon that expanded across her arm and down her chest every time she got a big check, Shelby insisted that tattoos were a manifestation of mindfulness – a sort of Be Here Now for the 1990s. They proved you were living fully for yourself in the moment, she said, rather than feeling anxious about the future or what others might think.

In an effort to improve her self-confidence, Sara dabbled in belly dancing. One young woman in her class had a detailed ring of autumn leaves running around her hips. When she danced, they rippled like the wind was blowing through. But Sara, who never married or had a child, kept thinking what it would happen if she got fat or pregnant, and the skin would stretch across her belly, dragging the delicate work into orange blobs.

About the same time, Lauren dated a guy who had three tattoos: a Wile E. Coyote from his 18th birthday; a Celtic knot inked his early 20s; and the words “To Be,” that came during a theater phase. Lauren was relieved she didn’t have a dolphin.